Same Language, Different Accent: Hayfield Secondary Explores Globalism with UK Community Leaders

“This whole project unfolded because I reached out to Aisha Thomas on LinkedIn one day…”

And the rest, as they say, is — quite literally — history. Let’s fill you in.

Ariel Alford has been a high school social studies teacher at Hayfield Secondary School (FCPS) for four years. For three of these, DCAESJ has born witness to the transformative racial justice education work she’s fostered with her African American history students, the wider school community, and, as you’ll come to know, far beyond the school’s walls.

Jump back to 2022, we captured Black@Hayfield, a study of Black photojournalism that not only shone light on the powerful work of Black photojournalists historically, but turned an interrogative light to Hayfield for its lack of Black faculty and staff. While the project was driven by students, it also created space for the too-few Black educators at the school to join the chorus, “Black teacher pushout ends now! Hire and retain Black educators,” a demand coined by Black Lives Matter at School.

In 2023, Alford and her students again studied then modeled their subject of interest — the Black Panther Party. This time uplifting the Black Villages guiding principle and marrying ASALH’s “Black Resistance” theme, the class explored Community as Resistance by using the radical education and community care politics of the Black Panther Party. They facilitated teach-ins with middle school English students about the U.S. Black Panther Party.

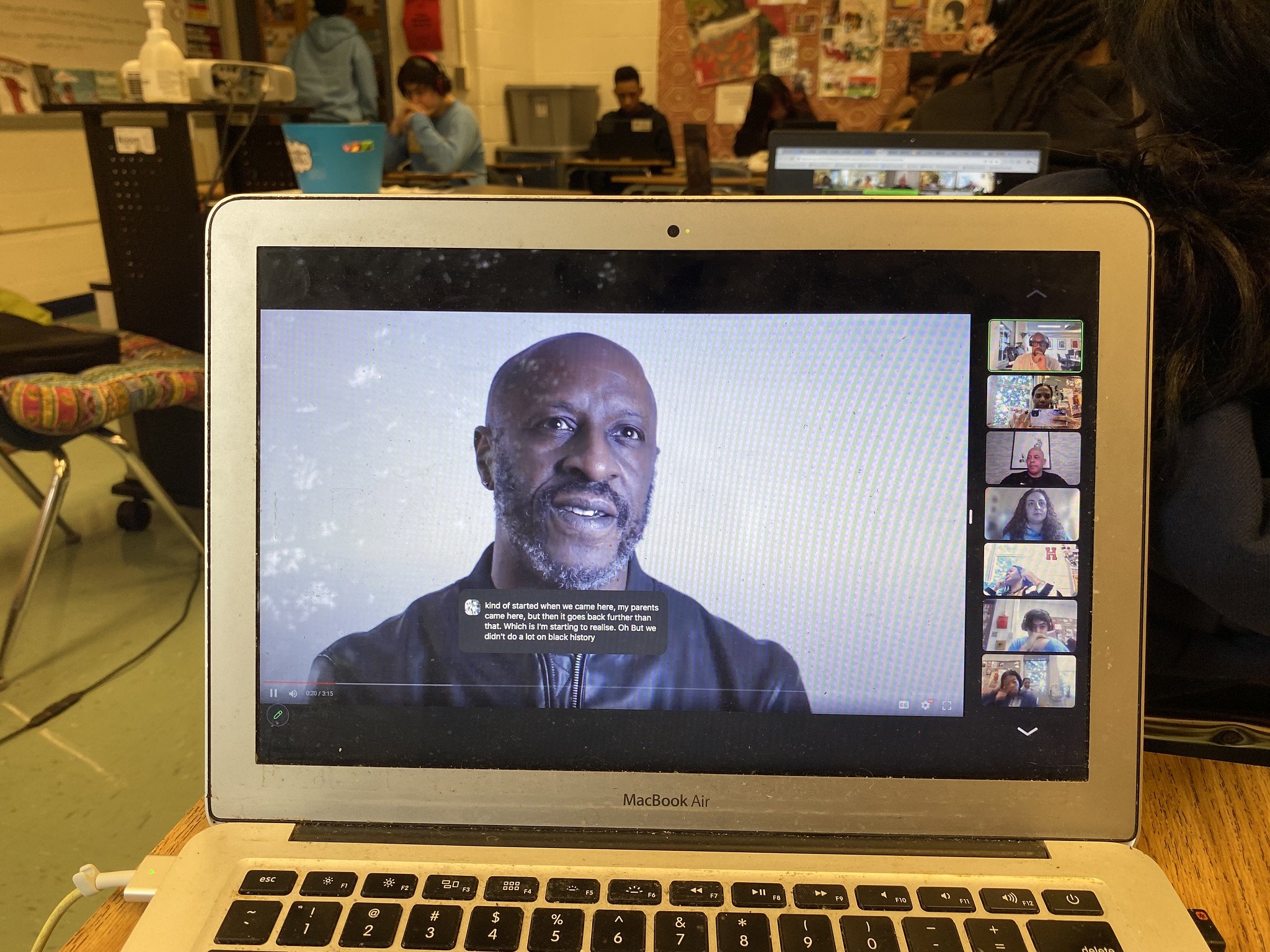

Sitting in her classroom in 2024, we were dazzled at how Alford has again expanded the reach of her class. From previous years’ insular yet impactful photojournalism project that reached 7th grade students, Alford again expanded her classroom by wrapping in two artists-turned-educators based in the United Kingdom to share their stories and curriculum modules designed to fill gaps and teach truths missing in the U.K. grade school curriculum.

Precious CARGO

Poet and educator Lawrence Hoo and filmmaker and creative director Charles Golding co-facilitated a workshop for Alford’s students. Together, Golding and Hoo created and currently lead CARGO Classroom, a virtual project that champions people of African and African diaspora heritage. CARGO formed in 2016 and is an acronym meaning:

Charting

African

Resilience

Generating

Opportunities

According to their website,

The CARGO Movement illuminates the contributions and achievements of people of African and African diaspora heritage, through poetry, illustrations, art installations, videos and educational resources, telling the stories of people who have catalyzed change and moved humanity forward.

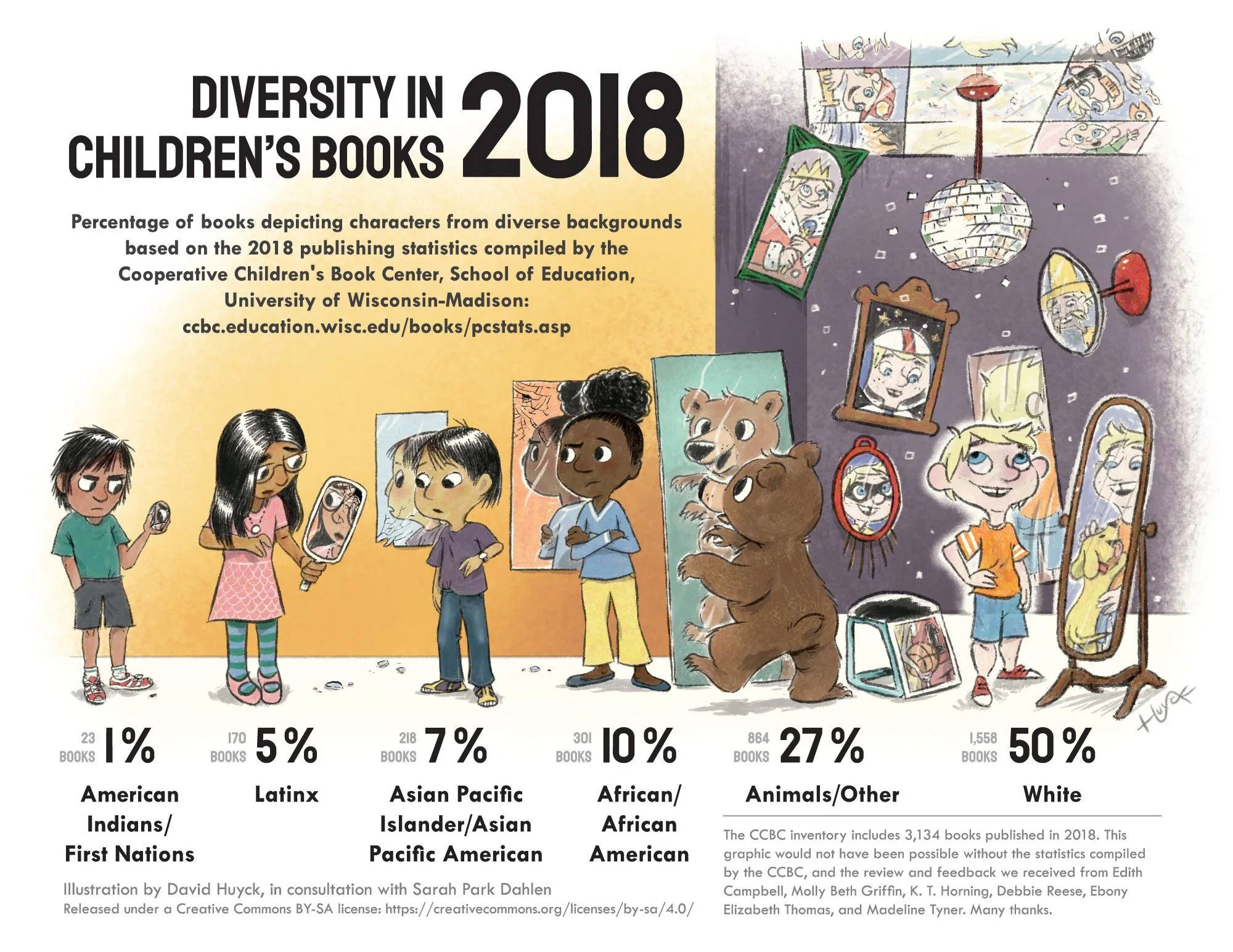

The original concept modeled their tangible modules after cargo shipping containers, reclaiming the horrific practice of enslaving and shipping people, and, instead, illuminating stories of people from the African diaspora that aren’t often told, or not told well. Hoo and Golding pivoted to a digital platform in 2020 because of the pandemic. At its outset, Hoo and Golding designed CARGO Classroom to address the missing parts of UK grade school curriculum, including:

The perspectives of individuals of African and African Diaspora descent

Recognition of the resilience, contributions and visionary leadership of individuals of African and African Diaspora descent

“You can’t wait for the state.”

~Ariel Alford

Why We Can’t Wait

In preparation for the virtual workshop, Alford engaged students in a thoughtful study about racial justice movements in the U.S. and the U.K. They drew parallels between historical episodes, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Bristol Bus Boycott. Alford again emphasized the powerful and often overlooked work of Black photojournalists, both in the United States and in the U.K., as a critical force in capturing these movements by exploring the radical work of photographers Neil Kenlock and Armet Francis in Photographing Black Britain.

For their workshop with Alford’s 9th–12th grade students, Hoo and Golding traced CARGO’s origins and evolution, painting a vivid picture of their own grade schooling experiences and how they envision CARGO directly responding to the gaps that still endure in UK grade school curriculum. They laid the foundation of their pedagogical practices, naming their intentional language choices:

The use of “African and African diaspora heritage” rather than “Black” and “European heritage'' rather than “white.” To avoid using language that refers to “race” because “race” was created approximately 500 years ago to divide humanity into higher and lower-valued groups.

The use of “enslaved people” rather than “slaves” because the term “slave” dehumanizes people of African and African Diaspora Heritage. By using the term “enslaved” we make it clear that someone took their freedom from them.

The use of “forced labour” rather than “work” when referring to enslaved people to make clear that slavery was not a consensual working agreement or a mutually beneficial relationship.

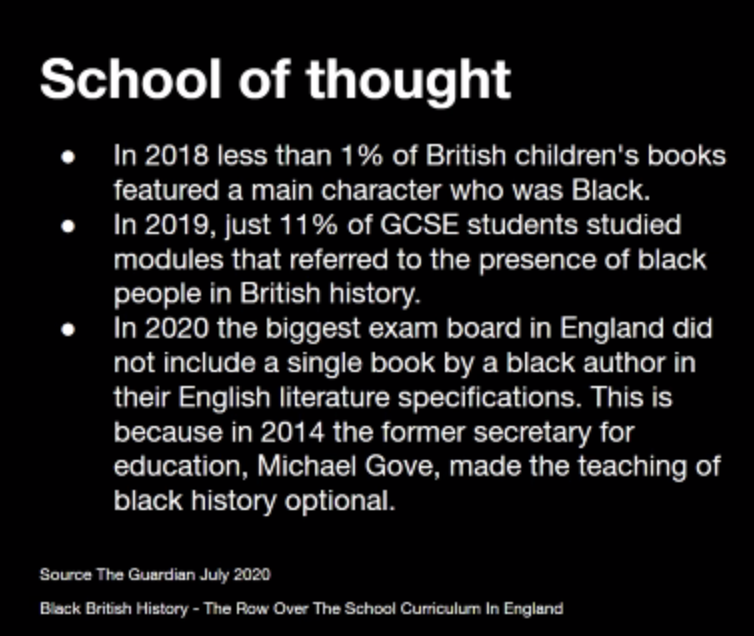

Hoo and Golding delved deeper into the workshop, uncovering history Alford’s — and many students based in the UK, for that matter — are not taught about. They echoed concepts introduced in Alford’s curriculum, including the long history of resistance from people of African and African diaspora heritage. They also further explored historical episodes they’d touched on previously, including the Bristol Bus Boycott. They guided students in learning about the Rampton Report, a 1977 report that found that “West Indian children as a group are failing in [the U.K.’s] education system” and that “'urgent action' was needed to remedy this.” Hoo and Golding then posed the question:

Why has so little changed for African and African diaspora heritage students in Britain between the publication of the Rampton Report in 1977 and now?

In response, students shared their heritages and how poorly they’re represented in the curriculum. Whether there are gross misrepresentations of their people, too much focus on singular “heroes,” or just a total erasure, Alford’s students lamented about how that negatively impacted them academically and emotionally. Alford’s course is a respite.

“We’re saying the exact same thing!” Ariel Alford

Globalism Principle

Between the two of them, Hoo and Golding went to school in the United Kingdom through the 80s and early aughts. Thirty plus years and thousands of miles away, but students noticed how eerily similar their schooling experiences are in 2024 as Hoo and Golding’s. Alford herself was not shocked, yet rightfully unsettled by the degree to which she, too, related to the stories Hoo and Golding shared. As both a former student of, then teacher in, the U.S. public schooling system, Alford knows the glaring issues all too well. She lamented, “We’re saying the exact same thing!”

Inherent in this collaborative unit study is an uplifting of a Black Lives Matter at School guiding principle: the Globalism principle. It reads,

We recognize that we're part of the global Black family in a common struggle toward liberation. We stay attuned to the different ways we are impacted, including our privilege as Black folx who exist in different parts of the world alongside our other contexts.

Alford, Hoo, and Golding together reified the robust similarities between past and present schooling experiences from their respective countries. While their educational spheres are thousands of miles apart, their issues with — and solutions to — education around people of the African diaspora are aligned.

See all of the images from the virtual workshop with Alford’s class.

Ariel Simone Alford is a high school social studies teacher at Hayfield Secondary School and a member of the DCAESJ secondary working group. You can follow her on Instagram at @educationandliberation

Vanessa Williams is a program manager for D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice.